Treating age-related hearing loss (presbycusis) may help protect some older adults from cognitive decline, according to findings from the first large, prospective randomized trial.

Previous research has suggested a strong correlation between age-related hearing loss and an increased risk for cognitive decline and dementia. Researchers have hypothesized that the distortion of sound signals reaching the brain, or changes in brain structure and function, could be reasons for the link.

"The study is very important as it adds to the growing literature on the topic that hearing loss is potentially associated with cognitive decline and hearing rehabilitation can potentially be used to treat risk factors associated with cognitive decline," said Elliot Kozin, MD, an otolaryngologist at Massachusetts Eye and Ear in Boston, who was not affiliated with the research team.

Initial findings from the ACHIEVE trial were published in The Lancet in July. Those early results suggested that interventions like hearing aids and auditory rehabilitation slowed mental decline in older adults with mild-to-moderate untreated hearing loss who already had lower cognition scores at the start of the study.

The findings were presented at the Gerontological Society of America (GSA) scientific meeting in Tampa, Florida. The trial enrolled adults aged 70-84 years who were either healthy volunteers recruited from advertisements (n = 739) or who had been recruited to participate in another study on atherosclerosis risk at a younger age (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC); n = 238).

The 977 participants, who did not have substantial cognitive impairment at the start of ACHIEVE, were randomly assigned to receive either a hearing intervention or a control intervention. The control, known as "successful aging" education consisted of individual sessions with a health educator covering topics related to prevention of chronic and infectious disease. Both groups underwent 6-month follow-ups over 3 years.

The researchers found no significant difference in cognitive changes between the hearing intervention and the health education control group. Both groups self-reported similar hours of hearing aid use and reduction in self-perceived communication impairment. The primary endpoint of the study was any change, in units of standard deviation, in a composite score of cognition based on a battery of neurocognitive tests overseen by a neuropsychologist.

But for a subset of the ARIC participants, hearing intervention reduced 3-year cognitive decline by 48% compared with the control group (difference, 0.191; 95% CI, 0.022 - 0.360; P = .027). The ARIC cohort were more likely to be older, Black, have a lower education level and income, live alone, have vascular risk factors for dementia such as diabetes, and have lower cognitive test scores at baseline.

Co-author Jennifer Deal, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology and otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, presented secondary findings from the trial at the GSA conference.

"We found that the intervention reduced loneliness and increased social network size over the 3 years," Deal said.

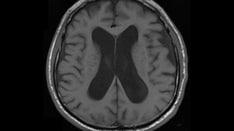

"We also found that the intervention protected against reductions in cortical thickness in the occipital and temporal lobes," which are related to cognitive impairment, she said.

Previous observational studies have suggested a link between hearing loss and cognitive impairment. But the most recent trial provides real-world data on participants who did receive a hearing intervention, which will help researchers better understand whether cognitive changes can be modified, according to Kozin.

"Hearing loss is not just about the ability to hear, but also the amount of energy and effort necessary to communicate," Kozin said. "When hearing is diminished, it requires an individual to spend a lot of energy focusing, such as lip reading and interpretating other communication cues. This is stressful and mentally taxing."

But for older adults without symptoms of hearing loss, inconclusive evidence supports screenings for hearing in primary care settings, according to the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

"While this study helps to add to the literature that individuals most at risk for cognitive decline may benefit from hearing treatment, additional research is needed to help guide clinicians and patients" who are not already facing cognitive issues, Kozin said.

The next phase of the study will continue to monitor participants for another 3 years, Deal said.

"We did find a group who did benefit from hearing treatment," Deal said. "What we need to understand now is who and why, so we can help individual patients understand if they might benefit or not from hearing treatment with respect to their cognition."

Deal and colleagues plan to assess the participants' cognitive functions and well-being and examine the effects of hearing interventions on aspects like social engagement, mood, and overall quality of life.

"Hearing loss is important for health. It's important for communication, social engagement and quality of life," she said. "And for some individuals, it may also be important for brain health."

Deal reports no competing interests. Various authors of the study report receiving grants from the US National Institutes of Health and the Eleanor Schwartz Charitable Foundation; consulting fees from Frequency Therapeutics and Apple; and honoraria from Oticon Medical, Sonova Holding, and Phonak USA, among others.

Lara Salahi is a journalist based in Boston.

Credit:

Lead image: Alexander Raths | Dreamstime.com

Medscape Medical News © 2023 WebMD, LLC

Send news tips to news@medscape.net.

Cite this: Treating Hearing Loss May Protect Cognition, but Only for Some, Study Finds - Medscape - Nov 10, 2023.

Comments